Small charities make a big contribution to personal, social and community wellbeing. So it’s not surprising that governments and big charitable foundations have been attracted to the idea of helping build their capability to do things better and their capacity to do more of it.

Over the years there have been plenty of initiatives of this kind. Evaluations tend to produce pretty positive findings – suggesting high percentage satisfaction amongst small charities with the support they’ve been given. But the extent to which they made a deep or lasting impression is open to question.

After all, small charities tend to remain small, independent minded and focused on issues that they feel that bigger organisations have ignored, neglected or even caused. So they’re often not minded to listen to the good advice of outsiders – however generously it may be dispensed.

Just because most charities are small, does not mean that they lack complexity. They may not have specialised divisions of labour, hierarchical command chains or bureaucratic procedures. But that does not mean that their internal dynamics are simple. In fact, small charities – especially when they are collectively governed and run – are complicated entities.

This is because many people invest their time and emotional energy freely and feel strongly about issues. As most small charities have few or no employees, there isn’t much scope to establish formally binding rules to constrain behavior. But this is not to say that they are flat structures – invariably there are power imbalances, producing pecking orders and factions – making the emotional life of the small organisation somewhat complicated.

If those people who govern and/or run small charities want to get on reasonably well, they must find a balance so that value conflicts, different levels of investment and the distribution of egotistical or altruistic spoils can be managed politely. I t seems obvious to me, now, that if someone from the ‘outside’ of this private world sets their sights on upsetting the balance by being intrusive and critical (as consultants must) – there’s a strong likelihood that there’ll be fireworks.

t seems obvious to me, now, that if someone from the ‘outside’ of this private world sets their sights on upsetting the balance by being intrusive and critical (as consultants must) – there’s a strong likelihood that there’ll be fireworks.

My recent study of the Lloyds Bank Foundation’s Grow pilot helped me to make some sense of all this. It was a very small study of just fourteen charities in two similar kinds of places: Neath Port Talbot in South Wales and Redcar & Cleveland in North East England. But the research was long-term and intensive, involving interviews and observations of charities, grant managers and consultants right through the programme. So while I’m flying a kite to explain what’s going on (hence the cover of the report) I think that I’m on to something.

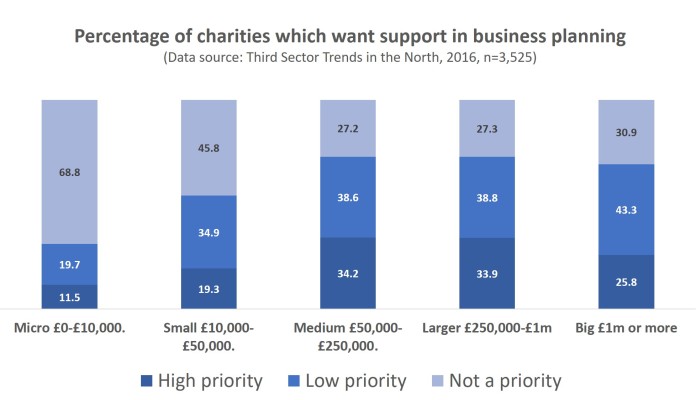

Big quantitative studies such as #ThirdSectorTrends show (see chart below) that smaller charities are less likely to want support to develop their skills than larger organisations. And when they do, it tends to centre on fundraising issues, not policies and procedures, strategy, business planning or managing people. It would be easy to brush this aside as being a simple matter of scale – of not having the time and energy to attend to these things – but I don’t think that explains everything.

In the ‘Grow’ project, ten consultants were commissioned to deliver support to small charities. The results were mixed. A few charities really went the distance and changed their ways of thinking – but not without a struggle. I’ll come back to that in a minute. Collectively-run charities responded best, while those led by driven and charismatic individuals changed little.

My feeling is that collectively-run charities did better because they have complex internal dynamics which demand that they deal with internal challenges and must find ways to solve or accommodate to them. But that does not mean that small charity boards welcomed consultants with open arms. Far from it.

‘They forced me to look at what I do and why. They pushed us in a lot of different and new directions. They challenged us to the point of us saying “sod off”. We felt that they hadn’t taken time to listen and understand us and what we wanted to do.’ [she/he] was a lovely [person], I liked them a lot, but s/he didn’t grasp who we are, instead, they wrote a PowerPoint – generic stuff – left me speechless!’

And yet, many months later, the charity was persuaded to frame their mission more clearly and allow this to shape new approaches to practice. Sometimes consultants were faced with a ‘wall of silence’ or out-and-out opposition which, had they not persevered, could have led them to abandon hope. Certainly consultants could find it frustrating when their ideas were flatly rejected.

‘[The consultant] wanted to do a strategy review; what are you for, what do you do well? That kind of thing. So we got on with it. At the end, the trustees just looked at each other – what was that for? We don’t have time for these little things.’ In this case, the charity initially found it hard to unstitch tried and tested (though not terribly successful) ways of working together – but after a period of turmoil – came around to the idea.

In some cases when opposition to support was implacable, consultants had little influence on the way charities were run. It is important not to brush such findings under the carpet – but take time to understand why. The most resistant boards put their trust in ‘luck’ or ‘fate’. They saw no advantage in business planning when they worked in a funding environment where they felt things ‘just happened’.

Such a view was explicable if it reflected how things had worked for them in the past. And, indeed, in one charity which was resolute in their opposition to their consultants’ entreaties, this is precisely what happened. Something unexpected came along, out of the blue, and secured their future in the medium term – reinforcing their view that ‘muddling through’ worked for them.

Broaching the subject of change in disorganised though well-meaning small charities was a sensitive issue. In one case, a charity’s desire to support their beneficiaries manifested itself as a ‘scattergun’ approach. As the consultant observed:

‘They think “‘something needs to be done, we need to help”, but they’re all over the shop – they do have skills, but they’re not connected – they all just do what they can do individually. If we get talking about managing change or proving value, they just say – “we just want to help”.’

The emotional balance in collectively-led charities was often fragile, especially if they were self-help groups where their members were under a good deal of pressure in their private lives. As their consultant observed:

‘They’re all up against it, so there’s quite a lot of argument on the board, it gives them something different to focus on, it’s an outlet for them. So I had to help them “tone it down, a bit”, make it a little less personal, and focus on some quick wins – to take steps that are achievable.’

In another charity I was told: ‘You have to understand, though, that the group is far more important to us than individuals, nobody can rise above it, it’s a shared enterprise. Trust is vital in the meetings, and when people stray off, it ruins relationships. To be honest, we’d had a few issues and didn’t know how to handle it. We’re now clearer about what to do and to how to do it better – to be more confident about the situation.’

Consultants could afford to be patient with collectively run charities and wait while negotiation went on behind closed doors. When the possibility of change was embraced, even by just one person on the committee or board, it meant that a debate had to be had. As one consultant told me: ‘I thought, at first, that they were refusing to do things, and they did say that; but really they were just scared of trying something new. They had to sleep on it, come around to the idea.’ Or as another consultant said: ‘They’re stubborn, but in the right way, they mull it over, then decide.’

Individually-led charities responded less well to consultants. Most leaders ‘stood their ground’ on issues they did not want to address (and most especially, sharing responsibility for the direction of their charity). And because there was no effective internal dialogue and reflection – the external challenge could be, and usually was, ignored or dismissed.

‘[the charity leader] does everything, they won’t let people do anything – so we did a risk analysis and they agreed that they were the biggest risk! They had no policies of any description, no volunteer policy, no confidentiality policy. There’s no plan of action. It’s all surface, no substance – it’s hard to tell if they can actually do anything.’

All too often, autonomous leaders’ unwillingness to share the burden sat comfortably, but not necessarily beneficially, with their board members’ contentedness to play a back-seat role.

When funding capacity building and change programmes for small charities, this research suggests, it is important to be respectful of and responsive to the ‘social dynamics’ of small charities and accept the need for patience while charity boards adapt to the idea of accepting help or effecting change. It’s not a point and shoot exercise.

It is a slow process. In an interview about halfway through the programme, one charity said to me that ‘We didn’t need a presentation on how to do a SWOT analysis,’ and they complained that ‘a lot of what we thought we were getting just hasn’t happened.’ I challenged them on these observations by asking them if they could really have achieved what they wanted more quickly, or did they need to have a bit of a fight first before they could get started? ‘Maybe,’ they conceded with good humour, ‘we’re stubborn, we think we know what we’re doing, blinkered, you might say.’

The full report from the Lloyds Bank Foundation Grow Pilot research can be found here